Filed under: A Lateral Projection

A NOTE FROM THE WRITER…

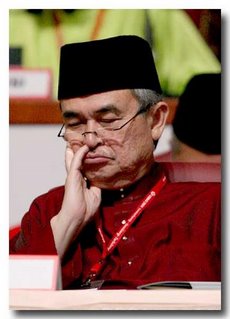

Here are two essays regarding the role of photographic images in our lives. I used the photograph “Pak Lah Tidur” and Malaysia’s 2008 general election as exampls (though facts may have been over exaggerated for added effect). Essay 1 esteems the role of photographic images while essay 2 deconstructs. I submitted essay 1 as my final draft but I still like essay 2 nonetheless (simply because I don’t think people realize how nothingly nothing photographs are). My lecturer however said that deconstruction, and being a nihilist for that matter, will only cause me to produce “Oh” essays because they make everything so meaningless they aren’t interesting to read. For that matter, she challenged me to write the exact opposite. Do however bear in mind that these are drafts and so a lot of words and points are recycled and appropriated differently.

ESSAY 1: THE PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE AS THE WAY WE SEE THE WORLD

To intrude the flux of time, if even for the flick of a moment, and to seize a single spectacle, such are the characteristics of photography in that it is both a marvel and an issue; its early years as the crest of modern science witnessed excitement and hope for the advancement of civilization while its latter days beheld instead, an increasing dilemma. This dilemma can be broken down into two parts. The first is that of photographic validity, that the very act of framing a single spectacle required the ‘unframing‘ of everything around and in front of the selected spectacle meant that photographic images can never provide a complete view and hence, never convey complete truth. The second is how photographic images have now become an integral part of society, a cornerstone to the mind and sight of the modern world. Highly esteeming photographic images, we have unconsciously largely assimilated them into our lives and in doing so, eventually elevated them as influencers, influencers with an indefinite range of effect as it can be as trifling as to cause the breaking up of couples (as in the case of scandal pictures) or as massive as to result in the proliferation of multi-billion dollar corporations (as in the case of advertisements).

This dilemma concerning the photographic image’s massive influence and lack in veracity, by which Christopher Phillips addressed in his essay Necessary Fictions: Warren Neidich’s Early American Cover-Ups as “[occupying] an increasingly unstable place in the systems which today generate cultural memory,” can be seen in the photograph above. Titled Pak Lah Tidur, Malay for “Sleeping Mr. Lah”, the picture depicts Malaysia’s 5th prime minister Tun Abdullah bin Haji Ahmad Badawi poised in deep slumber during a major political conference. The photographic image’s influence on the 2008 general election was monumental as it simultaneously aroused national controversy and instigated Barisan Nasional, the ruling party’s fall from grace. Despite Barisan Nasional’s efforts at repudiating the validity of the photograph, the people had sought to allow what they saw to influence their voting decisions. For this fact, it suffices to say that Pak Lah Tidur’s influence over the election is due solely to the general citizens’ interpretation of the picture.

Unfortunately, not everyone agrees with this point of view. Those who are opposed to it are prone to argue that the photographic image is simply a scientific documentation of visual data, a reproduction of the impression of bouncing lights that does not seek to influence nor convey anything other than the plain data it presents. From this deconstructive point of view, a photograph does not evoke emotions nor does it attempt to reveal any ideas or thoughts, but merely informs the viewer with descriptive facts regarding a spectacle. Any information before and after the presented data is irrelevant when reading a photographic image because a photographic image is but a single documentation of a single moment and thus, should be seen solely within the context of that particular moment. From this perspective, the photographic image Pak Lah Tidur does not depict a prime minister who is asleep, since for such a depiction to be possible the viewers are required to assume what went before and after the moment the image was snapped. Rather, it informs precisely the simple truth of the moment: the prime minister’s eyes were closed.

According to this perspective, the operations of photography as merely a process of visual documentation and the higher operations of “interpretation” as strictly a faculty of the mind are two distinct operations and should not be recognized as one. This perspective sees the aforementioned dilemma concerning the “unstable” role of photographic image in our current society as ultimately the ramifications of society’s unreasonable expectations of what the camera ought to be. That is, as we ridiculously will ourselves to perceive connotations out of a visual record containing only denotations, we inevitably end up with various interpretations and assumptions of a single photograph, resulting in illusionary influences that are unrelated to the photograph since the influences sprout not from the photograph but from the very minds of the viewers, and a growing weariness regarding the photographic image’s validity since a consensus cannot be reached between the many interpretations and assumptions meaninglessly made.

I believe however that the “human experience” in viewing a photograph cannot be denied. The deconstructive perspective fails to realize that even though it is easy to theoretically distinct eye from mind (to untangle denotation from connotation), in practice, we are essentially creatures of intellection and will for that very fact, inevitably perceive the world via “interpretations”. Photographs then, will always bear more than “bouncing lights”. In Reading American Photographs, Alan Trachtenberg, distinguished professor of English and American Studies at Yale wrote that just “like the natural objects themselves, [photographs] will therefore be surrounded by a fringe of indistinct multiple meanings.” Indeed, in the picture Pak Lah Tidur, although the popular interpretation made was that he had slept throughout a national conference, various other interpretations can be made nevertheless. To cite a few: prime minister Mr. Lah was probably only sleeping during the conference’s 5 minute break; perhaps he was tired and was just resting his eyes; or, perhaps he just has the habit of closing his eyes when he’s digging his nose. Though these interpretations are equivalent in plausibility, the majority of malaysians had opted the first interpretation instead on account of the fact that throughout Mr. Lah’s years as prime minister, Malaysia had witnessed a persistent decline, if not a stagnation in its economical growth as opposed to when it was under the administration of the 4th prime minister, Tan Seri Dato Dr. Mahathir.

Furthermore, Tractenberg also noted that in “representing the past, photographs [also] serve the present’s need to understand itself and measure its future.” That is, as society interprets a photographic image, the interpretation may serves as a benchmark to assess the present and in doing so, aid decision making for the future. In kind, the photograph Pak Lah Tidur was both a representation of the country’s downhill glide and an outcry for change. Thus, for the first time in Malaysia’s history, the national election’s result greatly disfavored the ruling party Barisan Nasional as major cities fell under the rule of oppositional parties and by virtue of that, Barisan Nasional lost its hold over 2/3 of the seats in the parliament, forfeiting its arbitrary control over the country in which it had retained for over more than 40 years prior to the year 2008.

And while there were attempts by Barisan Nasional to exonerate prime minister Mr. Lah from accusations of incompetence and ineptitude, I personally think that photographic images’ truthfulness should not at all be a point of debate. Taking a cue from Trachtenberg, photographs are “as enigmas, opaque and inexplicable as the living wold itself…” In other words, since the world is by itself extremely vague, photographs will simply be a limited reflection of that vagueness. That being the case, to sought truth from a photographic image would certainly be a futile act. This is why I would rather not question the veracity of every picture I come across and instead, in savoring the experience, allow the photographic image to, as Trachtenberg expresses: “entice [me] by their silence [and] the mysterious beckoning of another world.”

In kind, Pak Lah Tidur had transcended the pursuit for veracity in that its indexical signs merely retained their forms and acted as empty signifiers, waiting to be filled with new meanings by every pair of eyes it came across. Barisan Nasional however had failed to comprehend this. They had instead focused their arguments solely on an isolated event (Mr. Lah wasn’t sleeping in a conference!) while citizens on the other hand, were not at all concerned with the truth behind the photographic image because they had appropriated the image to hold multiple significations, and that one of these signification was that the image was appropriated a representational icon of the ruling party. For that matter, Barisan Nasional would’ve been better off holding their silence and working towards bettering the welfare of the nation than they would making a ruckus over the photograph’s “truthfulness”.

ESSAY 2: “THE CAMERA NEVER LIES” AS A PRODUCT OF DECONSTRUCTION

The camera is just a device. Mechanical or digital, the fundamental principles that govern the mechanisms of photo-imaging are essentially the same. Light that bounces off the surfaces of objects are “captured” into a single frame and are developed and reproduced onto prints we call “photographs”. Very much like the scientific operations of the human eye, the camera functions as merely a tool for obtaining visual data. Processed, these data are then documented as photographs. Taking a cue from James Agee, author of A Way of Seeing: An Introduction to the Photographs of Helen Levitt, “The camera is just a machine, which records with impressive and as a rule very cruel faithfulness…” In other words, the camera’s mechanisms of photo-imaging is strictly objective. It does not have a mind of its own.

In the photograph above, viewers witness the 5th prime minister of Malaysia sleeping during a major political conference. One of the most popular photographs circulating the internet during Malaysia’s 2008 general election, “Pak Lah Tidur” aroused national controversy and is believed to be one of the instigating factors of Barisan Nasional, the ruling party’s fall from grace. And while there were attempts by Barisan Nasional to exonerate prime minister Tun Abdullah bin Haji Ahmad Badawi from accusations of incompetence and ineptitude (and this they did by repudiating the validity of the photograph, saying that the picture has been digitally manipulated to deceive), voters of the opposition had obviously came to the realization that Malaysia isn’t Hollywood. Certainly we do not have the photographic technology to induce our “attentive” prime minister into entering a state of repose. For this reason, the only plausible explanation would be that “Pak Lah Tidur” is ingenuously a snap-and-process photograph. And while Barisan Nasional’s argument echoes Christopher Phillips’ line of thought, who in his essay Necessary Fictions: Warren Neidich’s Early American Cover-Ups, states that “photographic image occupies an increasingly unstable place in the systems which today generates cultural memory”, I however happen to disagree. As long as a photograph isn’t digitally manipulated, it will always be an impression of the truth. “Pak Lah Tidur” is thereby a visual documentation of an actual occurrence because the processes of photo-imaging simply do not permit the act of lying.

Unfortunately, our contemporary mindset obstinately insists that there’s such a thing as a “lying” photograph and in holding this conventional opinion, is quick to exonerate the camera from blame of perjury and have instead victimized the operator. We content ourselves with the believe that the cameraman is the sole culprit behind every “lying” photograph simply because he administers the entire processes of photo-imaging. This conventional opinion is as Agee encapsulates: “…it is doubtful whether most people realize how extraordinarily slippery a liar the camera is. The camera is just a machine, which records with impressive and as a rule very cruel faithfulness, precisely what is in the eye, mind, spirit, and skill of its operator to make it record.” Subduing the camera’s objective nature to the operator’s subjective nature, Agee’s claiming that the camera’s objective is to capture the operator’s subjectivity. In other words, he believes that the camera is subjected to the operator’s bias and thus, is incapable to objectively portray truth. I however, am opposed to this line of thought. Believing rather in the very antithesis of Agee’s line of thought, I gather that the nature of the camera will always inevitably objectify the cameraman’s subjectivity. That is, while the spectacle chosen for capture is subjected to the operator’s will, nevertheless, the moment the shutter flicks, the camera is bound to capture the moment’s truth. It is as Alan Trachtenberg, distinguished professor of English and American Studies at Yale, expresses in his essay Reading American Photographs: “photographs are still “bound to record nature in the raw”.” Ultimately, this concept of “nature in the raw”, or what I call “the moment’s truth” is exactly what Agee failed to realize when he labelled the camera “a slippery liar”. He had failed to realize that since a photograph is but a single visual documentation of a single moment, it should be seen solely within the context of that particular moment.

Take the photograph “Pak Lah Tidur” for instance, even if the photographer had intended to deceive the entire nation by exclusively recording that one single instance the prime minister briefly rested his eyes (so that viewers are given the impression that the prime minister had dozed off indefinitely throughout the national conference), the cameraman still didn’t lie. He had instead ironically and inevitably captured the simple truth of the moment: the prime minister’s eyes were closed. Whether the prime minister was sleeping or not, the photograph does not report because it only retains visual informations of that single brief moment. Thus, even if the operator had intended to lie, he can’t do so because there’s no such option. To such a degree, the photographer of “Pak Lah Tidur” didn’t lie. He had simply captured the moment as precisely as it is.

Thus, “Lying” photographs are simply ramifications of our unreasonable expectations of what the camera ought to be. As photo-imaging is assimilated into our lifestyle, our high regard for it had caused us to fail to realize that the camera is merely a parody of the human eye, sharing equal functions and limits withal. And thus, in blindly elevating the camera we inevitably fooled ourselves into thinking that one of the functions of photo-imaging is to preserve visual memories. We rely heavily on this illusionary task we assigned the camera with and through time, developed high expectations for the camera to “accurately” conserve and depict visual memory. As a result, when the simple truth within a photograph fails to live up to our subjective expectations of “accuracy”, we label it a “lying” photograph.

Marita Sturken’s essay The Television Image: The Immediate and The Virtual is built upon such absurd expectations. She contended that “television images have a slippery relationship to the making of history” and in substantiating this claim, presented her readers the Night Sensor Image of Baghdad Persian Gulf War, 1991 photograph. She explains that the image “was initially mythologized in the media as depicting Allied Patriot missiles shooting down Iraqi SCUD missiles headed for Israel and Saudi Arabia.” This however, was not the case she added. Rather, what the picture actually depicted were “the SCUD missiles coming apart at the end of their flight and falling into pieces onto the Patriots.” Sturken claimed that even though the truth had been revealed to the public, the public had instead chosen to archive the erroneous version. Phillips’ line of thought is also the same as that of Sturken’s when he wrote: “photographic image occupies an increasingly unstable place in the systems which today generates cultural memory”. Here, Sturken and Phillips have done precisely what I had mentioned above. They had chosen to discern the documentation of visual data and the interpretation of visual data as one.

Failing to distinct the operations of photo-imaging as merely a process of visual documentation and the operations of “interpretation” as strictly a faculty of the mind, they had expected photographs to convey informations beyond the visual data they blatantly present. For example, Night Sensor Image of Baghdad Persian Gulf War, 1991 shows precisely what it captured: blue flashing lights. Still, notwithstanding such straightforward visual facts, we will ourselves to see more. Ridiculously perceiving connotations out of a visual record containing only denotations, we end up with various interpretations and assumptions of a single photograph. And as a consensus cannot be reached regarding the photograph, we resort to labeling it as being “slippery” and “unstable”, concomitantly discrediting the truth it presents. Reiterating a point previously made: “lying” photographs are unquestionably the ramifications of our unreasonable expectations of what the camera ought to be. In other words, if we do not expect to see more than that which is presented straightforwardly within a photograph, we will realize that there’s no such thing as a “lying” photograph. From this perspective, Sturken and Phillips’ common line of thought is ipso facto, utterly obsolete.

Nonetheless, as I contemplate the photograph Pak Lah Tidur, I can’t help but laugh at the fact that a single photograph could possess the power strong enough to stir a national controversy. Indeed, we’ve by some means unconsciously allowed photo-imaging to play such an immense role in our lives so much so we’ve indirectly transformed it into a tool of power. This power has an indefinite range: it can be as trifling as to cause the breaking up of couples (as in the case of scandal pictures) or as massive as to cause the proliferation of multi-billion dollar corporations (as in the case of advertisements). The magnitude of a photograph’s power lies in its ability to incite us to make the worst, or best interpretations and assumptions regarding a presented spectacle. In the case of Pak Lah Tidur, the photograph wields political power and more often than not, incites viewers to assume that the prime minister is in deep slumber and consequently, prompts them to interpret him as being “incompetent” and “inept”. Hence upon these common assumption and interpretation of the prime minister, Malaysia witnessed a major political dispute.

Works cited…

Agee, James. “Ways of Seeing: An Introduction to the Photographs of Helen Levitt”. Reading Culture: Contexts for Critical Reading and Writing 6th Ed. Eds. Diana George and John Trimbur. Boston: Pearson, 2007. 238-242. Print.

Phillips, Christopher. “Nescessary Ficitions: Warren Neidich’s Early American Cover- Ups”.Reading Culture: Contexts for Critical Reading and Writing 6th Ed. Eds. Diana George and John Trimbur. Boston: Pearson, 2007. 471-473. Print.

Sturken, Marita. “The Television Image: The Immediate and the Virtual”. Reading Culture: Contexts for Critical Reading and Writing 6th Ed. Eds. Diana George and John Trimbur. Boston: Pearson, 2007. 488-493. Print.

Trachtenberg, Alan. “Reading American Photographs”. Reading Culture: Contexts for Critical Reading and Writing, 6th Ed. Eds. Diana George and John Trimbur. Boston: Pearson, 2007. 509-510. Print.

Leave a Comment so far

Leave a comment